- Home

- Aida Salazar

Land of the Cranes Page 3

Land of the Cranes Read online

Page 3

the one signed and dated

Betita-September 17

Ms. Martinez’s handshake is

warmer than yesterday’s.

She holds my hands between

hers like an empanada

in an oven

and blinks her small lashes.

Do you have any questions, Betita?

Before I can cry, I ask:

Why would ICE take my papi?

He only works.

Hurts nobody.

Will they make him go back

to the mountain where

mean men can hurt him?

Back to an Abuelita Lola

whose soft wrinkles

we aren’t supposed to know?

She hugs me and answers,

They might, sweet Betita.

Those who make laws don’t care

how much your father gives.

Their laws are not always fair.

But there are others who might help him.

They are fighting for all those who migrate.

Two days since I’ve seen Papi’s smile.

My own smile hides beneath my sadness.

So, I tug the cut pillow cloth

up

to my nose

and smell

the trace

of his feathers

in the cotton.

Mami tells our flock

after three days they finally found

where they are keeping Papi.

Tía Raquel brings us

caldo de verduras and tortillas

enough for the whole week.

Tío Juan brings us

people in suits

(lawyers, they call them)

who remind me of Ms. Martinez

with the way they speak

Spanish to Mami

English to themselves

though Mami can speak both.

I only catch one of their names … Fernanda.

I don’t understand

so many words.

“Petition,” “failed to appear,” “political asylum,” “deportation”

only that Papi will be

put on a plane and flown

to Mexico.

Papi will not be able to

come back to us

for ten years, if he is lucky.

Fernanda explains,

He failed to appear in court

to have his petition heard.

It calls for immediate deportation.

But he didn’t receive notice!

Mami’s explanation collapses like

the crushed tissue in her hand.

What about ours?

Yours is still current but I will

also file for political asylum.

There is no telling how long it will take

or if your case will be approved at all.

Or, we could go

meet him in Mexico

a place too dangerous

to call home.

Time is slipping.

Mami has to decide.

She cups her hands

over her tummy

and lowers her face

to the ground.

Our flock huddles around Mami

touches the brown tips

of their wings together

and holds her

while she cries.

Papi once told me,

The Nahuatl name for brown cranes is tocuilcoyotl.

Some lighter cranes cover their feathers

with mud to hide from predators while nesting.

I want to run out

to our yarda

and make a mud pile

so big

there is

enough

to cover

our entire

duplex

from

the

world.

Mami sends me to school

with Diana and Amparo.

She has been sick

in the bathroom

all morning.

A rope of knots

turned in my panza too

when I helped Mami

to bed

before I left.

As I walk, I wonder

if the plane Papi was on

flew higher

than the travel paths

of birds.

I wonder if Papi

is with Abuelita Lola yet

though we aren’t

even supposed to call

her on the phone

because they might

find us.

I wonder if he was allowed

to take his hammers with him

to help him fight

if the cartel

comes for him.

I wonder if he’s hiding

in the mountain

in a nest

built of mud.

I wish we were

with Papi

and I didn’t

have a Mami

so sad, she’s sick

and alone

in bed.

Diana says,

Be patient with your mami. On top of everything else

the new baby she’s carrying is turning her upside down.

A baby, our own egg?

Why didn’t she tell me?

Oh! I’m sorry, Betita. I thought you knew.

I shake my head and bite my lower lip.

Maybe ’cause she didn’t want to worry you.

It’ll be okay, Betita. She’ll feel better in a month or two.

I don’t understand

why Mami and Papi

keep things from me.

Hey, it’s good to be an older sister!

Babies are squishy all over and they

giggle when you act goofy.

Amparo opens her eyes wide.

But then, I don’t hear Amparo anymore

because I think about the color

of the shell around Mami’s baby

inside the nest of her body.

I worry because now we have

another thing to hide.

I worry.

How will we ever move a wounded nest?

Ms. Martinez calls us

into a circle at the reading carpet

and Principal Brown is there too

and so are some people

in fancy clothes

called social workers.

It turns out ICE stands for

Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

They are the ones doing “round-ups”

collecting birds in cages

clipping their wings

and sending them back

to where they were born.

Ms. Martinez encourages us

to make a picture poem

or talk if we feel like it

or cry if that’s what

turns inside us

scared tears

worried tears

questioning tears

crane tears

and we do.

They give us instructions:

Make a family plan

in case someone in your

family is rounded up

in a work raid.

There is no comfort in

what the fancy clothes say.

When Pepe raises his hand

to ask, What about learning math today?

Ms. Martinez looks at him

with eyes so heavy they looked closed.

We are learning about one another.

About the hurt in our hearts.

Sometimes, that is the most

important thing to learn.

I reach into my chest and softly

touch Papi’s pillowcase square

that now begins to smell more

lik

e my feathers

than his.

I want to go home

and put his pillowcase

in a jar

so I can save the smell of Papi

until I can

see him again.

I wish I knew

what Mami is going to do.

Will she make a plan for us?

Will we have to wait

all those years

or will we go

find him

hiding

in the

mountain?

I decide to cut half

of Papi’s pillowcase

and put it in a jar.

The other half I leave

on the pillow where

I now sleep with Mami

who is so sick

she can’t take care of

the rosy-cheeked twins

this week.

Mami looks at the app

on her phone that tells

her how much money

we have in the bank.

Our money is running out, she says.

She sings me a song

about a paraíso

with her sweet voice

before bed.

She cries into her

own pillow when

she thinks I am

asleep.

We finally hear from Papi!

Mami’s hand shakes

so she hits speaker, sets it down

for both of us to hear.

I had to stay away

from the mountain, mi vida.

Se corre mucho peligro allí.

It is too dangerous there.

His voice is crashing

and crumbling

through the phone.

I’m in the big city, Guadalajara.

Are you okay, Papi?

I’m with other cranes with broken wings

but we help one another.

He says he is sleeping on the street

and looking for work

scraped together enough

just to make this call.

I want to know if he has a pillow.

He tells me,

It’s okay, Betita.

I make one with my jacket.

I tell him about my pillow jar

and how I carry him everywhere.

He tells us about

his own secret money tin can

tucked in his cool gray toolbox

with money meant to surprise

Mami with a car.

Mami cries and promises

to put all of it in the bank

and send him some

so he can stop sleeping

on the street and so we

can come find him.

When Mami tells him

about the egg

she has in her nest

he cries too.

You’ve given me medicine

to heal what’s broken in me.

Papi tells us he loves us

and says before he hangs up,

No matter how we struggle,

remember to keep life sweet.

For the first time

in the two weeks

since they caged

my papi crane

I smile.

The next time

we speak

Papi’s got

his own phone!

Papi and Mami

decide

it is best

for Mami

and the egg

and me

to stay until

it hatches

and grows a little.

Mami has lost

two babies before.

They worry this one

might get lost too.

Then, we can be

with Papi again.

Together.

We make a plan with Diana

like Ms. Martinez and

Principal Brown said

in case

ICE ever

takes Mami at work

and I am

left alone.

We make a box

of our treasures,

a cajita for Diana

to keep safe.

Mami calls our box

proof.

Proof of what? I ask.

That we exist and

that we are good.

Mami shows me

and explains so I know too:

our petition paperwork

photos of us

Abuelita Lola’s phone number

our bank card

bills

medical records

our filed taxes

pictures of what the mean men did to your Tío Pedro

you are not allowed to see

and

this flash drive with

a digital copy of it all.

I add to the box of treasures

- the picture poem Papi never saw

- two jars:

Papi’s pillow jar

and a new pillow jar

I made

from Mami’s cut pillowcase.

Tío Juan and Tía Raquel

are on alert.

Diana now has keys.

She knows where

to find this cajita de tesoros

if the worst

ever happens.

Papi says he got the money

Mami sent him

I’m not sleeping

on the street anymore!

I have my own pillow too

but my wings are still

a little bit injured.

When I cry into

the phone he says,

¡Escríbeme, Betita!

Write to tell me

how your day went—good or bad

or how good the chocolate milk is

or how to spell your favorite words

or how big the egg is getting, okei?

But leave your sadness there.

Remember la dulzura.

I nod but he doesn’t see me

through the phone.

¿Okei, mi Betita?

I will, Papi.

I’ll send you

crane poems

every time

I want to

fly with you.

The first one I send him:

I draw

Mami and Papi’s bed

with smiley faces.

I write

I sleep on your smiling pillow

half of its case

is missing like front teeth.

Betita-October 9

I count six months till the egg

is supposed to hatch.

April.

Too long to wait to see Papi.

Maybe Papi will make his way

back to us before then?

Mami tells me,

Papi is looking for a job as an agrónomo.

A what?

A plant and soil scientist.

But Papi’s a builder and a dishwasher, not a scientist?

That is what he was before we left Mexico.

He’s interviewing for a job on an agave farm.

Is it far away from the mountain?

Yes, Betita.

No one knows who he is there.

Papi’s hammers won’t

be needed on the farm.

I wonder what other

superpowers

my papi has

that I’ve never known?

Mami is back with the twins.

She tells me she sings to them

again

like she used to do with me

like she used to do

when she was a teacher

in Mexico.

We teach through song

because it makes learning fun and easier.

Who doesn’t like a song?

It’s true.

/>

Mami learned the English

she knows by singing

pop songs on the radio.

She taught me

my colors

my shapes

my numbers

and multiplication

in Spanish

just that way

with her songs.

I’ve stuck into my memory

the address to the farm

where Papi lives now

because I mail him

the picture poems

I promised

to keep life sweet.

I make them during aftercare

when I expect him

to walk in

smile at me

reach out his

arms like ramps

ready to lift me up

but it is Diana

I see each day now.

I draw a heart

with wings

in the clouds

and the East LA

blue sky

with the words,

Quiero volar

en el cielo azul

contigo, Papi.

Betita-November 7

I draw a huge brown nest

with big eyes and long eyelashes

like Mami’s

holding a tiny egg

and me sitting

crisscross applesauce

beside it

like I’m meditating

holding his pillow jar

in my hands

with the words:

I wait

for the

baby crane

to arrive

and dream

to see you again.

Betita-December 12

On a Saturday morning without Papi

Mami and I walk through

our vecindad to catch the bus

to the community clinic

for her checkup

with Sandra, the nurse midwife.

Then to church.

I practice flapping my feathers

while I trot to keep up to Mami.

The elotero walks fast

past us too, the bells of

his cart chiming into

our steps.

But we stop him

to buy an elote on a stick

dripping in mayo,

cheese, and chile.

Señoras wash and sweep

their concrete porches

yell at kids

to move their broken bikes

talk to one another

over their iron fences

hold their arms

in a fold above their panzas.

An old man in a vaquero hat

rides a bike with a plastic crate

strapped to his handlebars

holding a real live chicken.

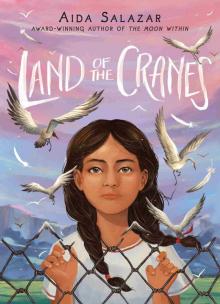

Land of the Cranes

Land of the Cranes The Moon Within

The Moon Within