- Home

- Aida Salazar

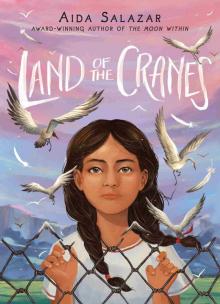

Land of the Cranes Page 2

Land of the Cranes Read online

Page 2

the sugary air across

the yarda and through

our windows

and into

our noses

and into

an

ahh.

Mami lights a candle daily

to a small statue of La Virgen de Guadalupe

and a picture of Tío Pedro faded in a frame.

His whole face is a smile.

His big wavy hair is like Mami’s

but shorter

and he’s got a reddish-brown

hair donut around his mouth

Mami doesn’t have

except for one whisker

that grows under her chin.

Can I light the match? Por please?

Con cuidado not to get burned, hijita.

She prays for protection under her breath

while she fusses with the roses

in the vase and the little milagrito

metal charms of hands and hearts

scattered at La Virgencita’s feet.

As I stare at Mami’s altar

I notice each time, we are

the brown of this Virgen

the morena of her

painted ceramic skin.

I spot the slice of moon

and the winged angel

that holds her up.

My favorite part.

I smile to think maybe

La Virgencita is a bird.

Virgencita llena eres de gracia …

Mami, excuse me, but I think …

… protégenos con tu manto.

La Virgencita has wings

like her baby angel.

Mami giggles

and pokes my panza.

Maybe she is hiding them in her robes!

Or behind her arms!

Our giggles tumble together

under La Virgencita’s patient eyes.

Mami. Is Tío Pedro with her?

Mami’s smile melts.

She nods her head a little

and stares into her brother’s picture.

Yes, mi’ja. He is with her now.

Ms. Martinez teaches me magic.

She casts the vocabulary words

all fourth graders should know

onto the white board

for us to squeeze into memory.

The funnest game.

I love to loop and lift

the lines to make shapes

mean something

on my paper.

Words in English

I don’t know at first

but the more I draw the curves

and lines, then hear the way they

sound out loud, the more alive

they are in my head.

Words like:

intonation or fortune

energy or angle

anguish or freedom

myth or alchemy

are the almost spells

I spell

with ink.

From my cushy bed

Saturday-morning sounds

are a blast of rancheras

swooshing into our house

leftover music from

Omar’s ritual car wash

and el paletero’s bell

ring, ring, ringing

and Papi’s calling,

¡Para arriba, Betita Plumita!

Los quince de Tina are today!

I squeeze my ojos shut

but my ears are two nets

snatching more sounds

the tiny cackle of Amparo’s baby brother

and the fart noises I know she makes

by catching air in her armpits

make me giggle

before Papi tickles my toes really awake.

I tumble out of my blankets

follow the smell of huevitos

and café coming from the kitchen

thinking about

my cousin Tina’s

round yellow dress.

I run into Papi

spin, spin, spinning

Mami away from the stove

he tucks her into a cheek-to-cheek

two-step ranchera

then pulls me

into a close snug.

I bury my face

into Mami’s squishy belly

feeling my mouth stretch

into the sappiest jelly grin

as I bounce

along to their

two-step ranchera strides.

When we sit to eat

I bring my paper and crayons.

Guarda eso, Betita, focus on eating.

Mami slides me my dish.

With a wink from Papi

I drift into my drawing.

Tina in her quince dress

her straight blue-black hair

that I use two colors to get just right.

I draw myself in my new

dusty-rose dress

holding her hand

my mouth so open

a fly is about to go inside.

Six raids in the last two days, Papi chews.

Where?

In the factories just over the tracks.

People say there will be more.

This administration is out to get us.

But this is a sanctuary state.

A what, Mami?

Papi clears his throat and

almost whispers,

A “sanctuary” is a place where cranes can’t get caught.

Caught for doing what?

They look at each other

and then at me.

I can tell I’m not supposed to ask

by the way their worried eyebrows

push down

on their blabber-mouth eyes.

For just wanting to fly, Plumita.

So can we get caught too?

Betita, Mami quiets me, eat up, cielito.

We have to get to church early

before the ceremony. Mira, look

at this beautiful bouquet I made from

our rosales for Tina to offer La Virgen.

I look down without their answer

and quickly draw a bouquet of flowers

in Tina’s other hand.

The only wordspell I have time to cast

is my curly name and the date

on the bottom.

Betita-September 15

I looove Tina’s fancy dress

big and bouncy golden-yellow satin

with sparkly flowers at the hem.

Her fanciness courtesy of

Mami and Papi

the padrinos of that dress

’cause they paid for all

but the last one hundred dollars

Tina’s dad, Tío Juan, threw in.

Tío Juan is Papi’s brother

and the first crane to fly here

a long time ago.

He helped Papi find a job in

construction, and Tía Raquel,

Tina’s mamá, helped Mami

find work taking care of babies.

They are part of the flock we have here.

Tina shows me her Gram page

with all the facial tutorials

she likes and uses me

to test them out.

Then we take pictures and videos of our

slathered green avocado faces

and cucumber eyes

she posts to her Gram story

and we wait for the likes to pop in

from her almost one thousand followers!

Funny to think what she might look like

in an oatmeal mask and poofy sparkly dress.

But right now

our happiness

is big and wide because she looks like Belle

dancing a waltz with gruff Tío Juan

in her Beauty and the Beast backyard ballroom.

Paper flowers all around the tall rented canopy

yellow ribbons woven into the chain-link fence.

Tía Raquel stops her running around

long enough to get weepy happy

and wipe her tears with the

corner of her plaid apron

over her lacy navy dress.

A bunch of Tina’s school friends

are here wearing so much makeup

and tiny dresses so tight, they look really old

like grown-up old.

Tío Desiderio is on guard

at the bar, making sure some

of her pimply-faced guy friends

don’t try to get beer.

Most of the smaller kids

are weaving in and out of tables

between the older tíos and tías sitting

on folding chairs and fanning themselves

because of the late-summer heat, but not me.

My eyes are drinking up Tina

floating

and

gliding

like a dancing crane.

I tug on Mami’s

dress and point at Tina and

then right back at me.

One day, I wish to have a

backyard Beauty and the Beast

ballroom crane quince

like Tina.

By the way Mami squeezes

my round cheeks

with her manicured fingers

I think she wants one for me too.

At aftercare pickup

Papi says,

Now that you are a fourth grader

it’s time for you to know

the meaning of the word

“cartel” in Spanish.

“Cartel,” a cardboard sign

to announce something

as in “for sale”

or “car wash here.”

But also,

a group of men who sell

drugs

guns

and people

sometimes.

A cartel hurt Tío Pedro

made him disappear

when he didn’t give them

the money they wanted

and then, wanted to come

for us too

though we had nothing

to do with it.

It’s why we can’t see

Abuelita Lola anymore.

We were lucky Tío Juan

petitioned for us

to be here before we knew

of cartels.

Petition?

It’s like getting on a wait list.

For what?

To fly free, Plumita.

When I ask Papi

if the men in cartels

are cranes like us

he says,

It’s impossible, Betita

because their souls

are so mangled

they have forgotten

how to be birds.

In Ms. Martinez’s class

Amparo invites me to play

a mapping game on a globe.

She tilts her round head

and her floppy ponytail whips

to the side when she asks.

I am always ready

to play with Amparo.

She explains,

Okay, Betita,

first I’ll find a random place

then I’ll spin the globe

and you have to find it.

Ready … Madagascar!

I find it easy.

Here!

This big island floating

in the sea next

to Africa.

When we switch

I run my fingers over

the bumps on the globe

that mean mountains

and continents

and make my fingers dance.

I start at Alaska

and feel the ridges

run into the Rocky Mountains

then turn into the Sierra Madres

the bumpy mountains connected

like a curvy spine

all the way down

the back of North America.

These are all the places

Papi said cranes fly.

Amparo snaps,

C’mon, Betita, give me a place!

Without looking I say,

Here, find Aztlán

and spin.

She squeezes

her hazel eyes

almost closed at me.

She knows it’s a trick question

but she goes along.

Ay, your papi says Aztlán

doesn’t exist in real life anymore.

That the Aztecs left it a long time ago.

Yes it DOES exist, tell me

where is it now?

She rolls her eyes but answers,

Okay, we are rebuilding it here in East LA.

Amparo points to LA on the globe

then she places her hand over

her chest and says,

También in here.

I get cartwheel happy

because Amparo

has been listening

to Papi’s stories!

She knows

she is a crane too!

On Monday

Papi must be late. It’s six p.m.

and aftercare closes at six fifteen.

The ticks on the clock

are honey-slow tocks

I try not to count.

I wonder if Papi’s broken a wing

on the skyscrapers he helps build

with hammers and steel?

I wonder if Papi forgot

I am waiting and rushed

to the restaurant with too

many dishes to wash?

But that has never happened.

Ms. Cassandra, the teacher’s aide,

bends the creases of her forehead

near her phone when Papi doesn’t answer.

So she calls Mami, who is the nanny

of toddler twins with bright red cheeks

who can’t fly.

Ms. Cassandra gives me a tissue

to soak up my teariness because Mami

can’t come for me right now either.

She can’t leave those babies

until their parents get home.

Papi is coming, I whisper to myself.

I’ll tuck my wings close and wait.

When the hand of the clock

is past six fifteen and there is no Papi

the sun is still so bright outside.

Principal Brown drives me

to Mami’s work

as far away as forever from school

though close to where

Principal Brown lives.

She tells me,

Everything will be okay, Betita.

Your father probably got caught up.

I’m not sure.

I want Papi.

Where Mami works is so big

it could be a scraper Papi built.

As we arrive, Mami is closing

the wide wood front door behind her.

She wraps one arm around me.

Betita, nada pasa. Todo está bien.

Her face doesn’t match her words.

Something is happening, and it isn’t okay.

I don’t get to see inside.

I don’t get to meet the twins.

I don’t get to

see how

those who aren’t cranes live.

Thank you, Principal Brown. Mami’s voice breaks.

You’re welcome. Please let me know

if there is anything else I can do,

she tells Mami.

We walk to the bus stop

and watch Principal Brown drive off.

Mami is on the phone

now a faucet of drip-drop

tears falling on the pavement.

When I ask her what happened to Papi

she shakes her head

as if to say,

Not now, Betita.

From a string

of weeping words

I learn

someone named ICE

put Papi and other hammer workers

in a cage

and Mami doesn’t know

how to set him free.

I cry to think of Papi

unable to fly.

On the bus, Mami says

here in El Norte

there are walls we were not

supposed to cross.

We are sin papeles

undocumented, her voice trembles.

A word that means

“without permission.”

I remind Mami this is

the land of the cranes.

We have wings

that can soar above walls.

Sí, mi amor, but not

when they have cages

and can stop us from flying.

She sweeps me into

a one-handed hug and

kisses the top of my head.

I watch the traffic turn

from smooth to crowded

through the window of the bus

taking us home.

That night

I crawl into Mami and Papi’s bed

smell for Papi on his pillow.

I stare at Mama’s Virgen altar.

Will I ever see him again?

I take scissors and cut out a square

from his baby-blue pillowcase

tuck the cloth into my blouse

and secure it with a safety pin

near my heart.

I cut out another little piece

and put it on Mami’s Virgencita

smoosh it between the moon

and the angel

and pray for protection.

Please, Virgencita, don’t

take Papi with you too.

Mami is in the living room

with Amparo’s mom, Diana.

They are two cranes murmuring.

She arranges for Diana

to get me after school

until Mami comes for me

at their casita just next door.

Diana will never be able to carry

Amparo

her baby

and me

on her

tiny

shoulders.

Could I fly without Papi?

my crane poem

the one about

a poet bird, Juan Felipe

Land of the Cranes

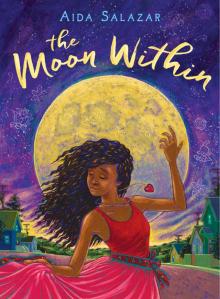

Land of the Cranes The Moon Within

The Moon Within