- Home

- Aida Salazar

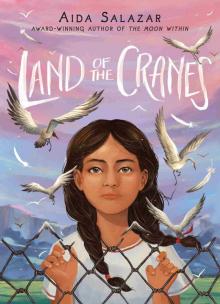

Land of the Cranes Page 5

Land of the Cranes Read online

Page 5

When I tell Mami,

Tengo hambre.

She looks down

into me,

Sí, mi amorcito, I am too.

That’s when I remember

growing a baby makes

Mami caterpillar hungry

and if she forgets to eat

protein, she gets

woozy headaches

and throw-up sick.

In a cage with what looks

like thirty mothers and children

Mami and I find

a little spot on the concrete floor

enough for one to sit.

Mami goes down first, then

pulls my hand

pats the space in front of her

for me to sit between

her legs.

She covers us three

with the silver sheets.

The others

watch us, closely

waiting for us

while we wait

patiently

for them to say

hello.

Mami searches the stare of a woman

opposite us.

We are eager for a smile

but that woman is empty of sonrisas

so Mami looks

to the next

and the next

everyone either too blue or sleepy

to find a way to make pursed lips

turn up

let a sun ray free.

Slowly cranes begin to lie down

pull their foil blankets over the

ghosts of wings,

arms, legs,

their children’s too.

The cold is too prickly to sleep.

Mami keeps searching for light

starts to receive shy nods instead

until finally a woman right next to us

with three children of her own

lets an hola

bloom in her mouth.

To imagine Papi’s frown

when he found out

we weren’t coming, but taken away

makes me dizzy with sadness.

I want to think of dulzura

like Papi always says

so I imagine we are

in a backyard ballroom fiesta

red, yellow, orange, and green

ribbons shoot through the air

weave themselves into the cages

wrapping us warm with waltzing smiles.

I think of happy Tina

and my one-day quinceañera

I think of spelling a spell

and Virgencita angels with wings

but the cold breeze

stops me.

I squint it away

and dream of ribbons, again

but the chill that rips

up my chicken skin

reminds me, stronger

that we are sitting

in a crowded cell

my little dulzura, dying.

She says her name is Josefina Ramírez

from a fishing town in El Salvador.

We missed dinner.

It’s a miserable tray of frozen vomit-like food.

Tomorrow you will taste it for yourselves.

She fusses with her baby

a round-faced brown crane chick

who scuttles and coughs into her side.

Is this how I should keep warm?

She says,

Pronto, the lights

will be out for the night.

But the flashlights will be in our

faces every hour. I’m not sure

what they are checking for.

One thing for sure

they never make it warm here.

Her chicks are

quiet when

they aren’t coughing.

Their faces are bright with rashes.

Their eyes blink like flickers

while they scratch their heads.

Their lips are purple blue with cold.

I pretend I am

a newborn chick too

and find the warmest

place to be beside Mami

and the egg.

The crinkle crackle of the blankets

slowly comes to a hush after a while

and I feel Mami crying like others

but the

cough

cough

cough of

Josefina’s chicks keep punching

the night

until that too

becomes a pounding

that stones me

to sleep.

I dream of Papi

flying

alongside me.

His bright black ojos glisten.

I see his wavy hair

pushed back by wind.

Mami is flying too

the egg under her.

The park and freeways

below, cars

like ants

we are so high.

All of us, soaring.

Then I see him fall

sudden

with the sound like a

firecracker

so loud it leaves a ringing

in my ears.

Then I fall too

though I flap

my arms

in a fever.

Mami falls

behind us.

I scream.

A wet red dot

grows in my chest

which I touch

with my fingers.

I sense we’ve

been shot.

By men in the mountain

below

I can’t see?

My heart is a speed train

inside my body

that bursts me awake.

Then, I see the safety pin

that holds Papi’s pillow square

is poking me and

draws blood.

I’m lying next to Mami

on the concrete floor.

My panza mumble grumbles

and my throat

feels like there’s

a big ol’ grapefruit

stuck behind my

tongue.

The lights come on

inside this cage

and a mass of silver

foil blankets

begins to stir

in the ever cold

of this hielera.

This is Yanela, Carlos,

and baby Jakeline,

says the mama crane

who spoke to us last night.

I sit up next to Mami

shiver as I lean into her

and notice their brown faces

soft, in the glowing white light.

I see the shape of their

broken wings

whose tips they use

to scratch

scratch

scratch

their heads.

Josefina pulls lil’ Jakie

next to her and begins

sorting through her hair.

I scratch, feeling all

of a sudden an itch

on my own head too.

Mami combs down my feathers

with her hands while we

listen to Josefina tell us

how they got here.

Things were so hard, bien duras, in El Salvador.

I had a food cart where I sold pupusas I made myself.

The marreros came and asked me to pay rent every month or else they would hurt my children. I paid the first month but the next month when I didn’t want to p

ay, they beat me right in front of baby Jakie and said they knew where Yanela and Carlos went to school. So I paid again though it left nothing for our expenses. Then I saw them kill a man for not paying the rent on his cart. I knew we would be next. We left that night. We hid in another town with my aunt. My mother sent us the money to pay the coyote to bring us to the border to turn ourselves in. But they locked us up behind these fences. Trapped like animals when all we wanted was a little help.

As we listen

the baby is now free-falling into

the older girl’s arms and giggles

so sweetly, but her sister

doesn’t break a smile.

Carlos, the boy, sways side to side

like he’s almost dancing

with a scowl at me

folded into

the raisin of

his thumb-sucking

face.

When Mami shares

how we ended up here

she holds me closer.

I try to tell Josefina about cranes

but Mami hushes me.

She whispers

to try not to cry.

Josefina shakes her head

while Mami talks

wrinkles her lips tight

tries to calm Jakie on her

lap again and keeps

dipping into the baby’s head.

Then, as if she’s caught something

between two nails

she presses until something

tiny, so very tiny, pops.

What was that?

She half smiles like she

feels sorry for me

because I don’t know.

Son piojos.

Lice are little bugs

people sometimes get.

Give it a few days here, mi’ja,

and you’ll have them too.

Carlos squints

at me, pulls the thumb he’s been

sucking out of his mouth,

and lets out a cackle.

The stinker.

Yanela, the girl,

looks down

the entire time.

She droops sad

like wilted flowers.

I offer a smile to Yanela

to try to grow dulzura

in a girl who could be my age

who could be a friend?

Her expression is

as still as steel.

Josefina sees me

reaching

into the soil of her daughter

wanting to plant a friendship.

She lifts Yanela’s chin

for a second

but as soon as she lets go

Yanela’s head buries

down

into the ground

like lead again.

Josefina takes a shallow breath

and wants to smile at us

but it is chased away

by her own gloomy voice

as she unravels more

of her story like yarn.

They took my niños from me

days after we arrived here the first time.

They called it “zero tolerance.”

I’ll never forget how they cried

as they pulled them away

with so much fear inside their tears

I could do nothing about.

Though I begged, day and night,

to have them back

they kept them from me for two months.

The longest, most painful days of my life.

I didn’t know if I would ever see them again.

I don’t know where they took them

or what they did to them.

I know one thing.

They were different children

when they finally gave them back.

They deported us to Tijuana the next day.

Now they caught us on our second try

to get to Los Angeles, where my sister

is waiting and has a place for us.

Qué pena, Josefina, I’m so sorry.

Mami taps the back of her hand gently.

Yanela pulls baby Jakie

onto her lap, circles her arms

around her sister, lightly

lays her forehead

on top of the baby’s head

like she wants to hide.

Baby Jakie wiggles her head

back and kisses Yanela on

the bottom of her chin.

I wrap the vines of my arms

around Mami’s steady leg

so afraid this hurt

will happen to us too.

I hear the unlocking of the gate

turn to see two guards with a cart.

One guard yells,

Burros, time to eat!

They called us donkeys, Mami,

I say to her in disbelief.

Though I’m starving

I grimace at them

but Mami wipes my face

gently with her hand.

I know she is hungry

by the way

she swallows slowly.

We line up to be served

a cardboard tray

holding a burrito

moldy and half-frozen.

Exactly how it feels

to be inside this prison.

I make a game

all by myself

with the cardboard tray

and the paper napkins

I keep.

I suck on small wads of paper

roll and mush them

into the shape of a bird

moist with my spit.

I pretend the tray

is a boat that sails

no

a nest.

I lay

the bird down

then stuff beneath

its little tail

a perfect oval egg.

Then I make a doll

whose legs I curl

beneath the bird

and turn her

face up

to look for

the bluest blue

in the sky.

I catch Yanela

looking too

so I mash together

another doll.

When I hold it up

to give to her

she turns

the other way.

One guard’s green-gray eyes are

a snake’s slithering in the grass.

He is not feathered.

He is not scared.

He is not caged.

He patrols and moves

his overgrown body through us

over and around us.

Circling.

Watching.

A badge with the name “J. Stevens”

like a dangerous mark

across his vest.

A gun holster like a rattle

shaking with each step.

He calls us burros, again.

Donkeys, but really it means stupid.

A word so hurtful Mami never

ever lets me use it.

Don’t whine, burros, we saved you from the desert.

He says it in perfectly

round Spanish

the kind of Spanish

that makes you want to

trust

because it is the Spanish

of Mami’s songs

and Papi’s stories.

I can’t get past

those beady eyes

and the hiss that hides

in every order

he gives.

Half a concrete wall covers a corner of the cage.

Every now and then I see people go in and out.

A toilet flushes and leaves a bitter smell

tells us someone just went.

Mami tells me, It is okay to go.

She’s gone twice in the night

’cause the egg pushes down on her bladder.

I don’t want everyone

to hear me

or smell me go

so I hold it

both number one and number two

until my panza hurts

and I cry as Mami

pulls me through

the cell to the toilet corner

so embarrassed

I bury my face

in my arm.

the toilet is piled high and

overflowing

with wads of toilet paper

from everyone’s wipes.

The stink stings my nose.

Mami moves to push

the paper pile down

into the can

with her foot

then wraps some paper

around her hands

and picks up

the other toilet paper wads

on the floor.

I’ll help you, I say

covering one hand

and with the other

plugging my nose

with the tips

of my fingers.

I notice some of the stains

peeking through

are red.

What’s that, Mami?

That’s blood from women

and girls on their regla.

I remember about

the cycles Mami told me

will one day

come to me too.

Pobres, looks like they are

using toilet paper for their necesidades.

We try to wash our hands

but the sink only drops

big drips of water.

Real rays, sun and sky

speckled by clouds

are a relief from

the freezing cold.

I hold Mami’s hand

and whisper

Mami, let’s fly

but she looks

at me with the saddest ojitos.

We can’t, Betita, remember

our wings have been clipped.

In the light, I can’t believe how huge

the white freezing monster is from outside.

I notice all of the fences

the guards at the edges

their guns ready on their belts

to stop us from leaving?

Let’s walk, mi’ja, get as warm as you can.

We walk past a group of kids

rubbing rocks on the ground

like chalk

and I wish to

draw something

write something

something big

an S.O.S.

a picture poem

maybe somebody will see

it and get us

out of here.

Maybe?

But I don’t want to leave Mami’s side for one second.

Mami sings while we walk

and I join in the smallest voice.

We move fast, so fast

sweat bunches up on our foreheads

until it is time to file back in.

Land of the Cranes

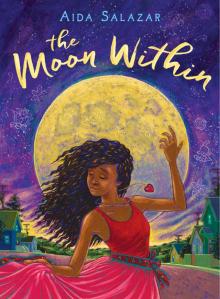

Land of the Cranes The Moon Within

The Moon Within